This is a time of year that often finds us lugging Christmas across the Yucatán. Last year, almost immediately after the bus pulled out of the terminal in Playa del Carmen we were interrogated by a foul-breathed and palpably frightened German backpacker, who had decided that he might want to explore the lands south of Mexico but knew only enough about them to set his pulse racing.

Obviously what we had to say was far from reassuring because he was soon scrambling up to the front of the bus to ask the driver to stop and allow him to get off in the middle of the peninsula's toasted (and largely uninhabited) scrub. This would have frightened me!

Resigned to reaching the border at Chetumal he went back to his seat behind us, but periodically leaned over my head to voice his trepidations and shower us with cold sweat.

He was visibly afraid of many things, but the thing that ultimately seemed to spook him more than anything else was the sheer quantity of luggage we were transporting with us. Providing him with deliberately vague explanations for this seemed like good sport at the time.

On arrival in Chetumal V negotiated a deal with a mini-van driver who would take us (and all our bags) as far as the Belize-Guatemala border for a remarkably reasonable fee − provided that we recruited a small group of fellow travellers to come with us as far as Belize City. This proved no major challenge for V and within the hour we had assembled a young Dutch law student, an Anglo-Indian solicitor (both bound for scuba adventures on the cayes), a deranged and loudly Islamophobic old Frenchman heading for Dandriga and our permanently cold-footed Kroutish friend.

Granted it wasn't the sturdiest of vehicles, yet all but he seemed genuinely enthusiastic about the prospect of the adventure ahead. I was the last to board and as I opened the door and slung in my heaviest bag there was a screech and the German disembarked in the instant, as if afraid that the door might shut again. We last saw him scuttling back towards the terminal, presumably to catch the next bus back to Cancun.

He might have been reassured by the landscape of northern Belize − undoubtedly one of the most well-manicured in all of Central America. The solictor had planned to fly to Caye Caulker from Corozal, but one look at the aeroplane awaiting him on the grass strip there and he cheerfully rejoined our company for the rest of the ride.

When we left smeggy old Belize City behind us and started to drive towards a sanguine sun setting behind the Maya Mountains, there was just the two of us: the driver and rather of lot of luggage left onboard. Although a card-carrying Mexican now, he had once been a chapin (Guatemalan) he reassured us. Soon he was questioning the logic of us stopping overnight in San Ignacio before crossing into Guatemala the next day: he himself had to carry on to Flores on Lake Petén Itzá − why didn't we come along with him and connect with one of the "first class" overnight services from Flores down to Guatemala City?

Prior to this one, the scariest roadtrip I had ever experienced was on that very same road through the dusky rainforest back in 1988. Much younger and with only two weeks' experience of the developing world behind me (and absolutely none of war zones), this solo jaunt into Guatemala really was a ride into the unknown. The first serious novelty was having an AK-47 pointed at me by a jittery-looking teenager as everybody on the bus was made to get down and present their papers. To this day I'm not sure if this rude interuption was staged by the army or the guerrillas, but as a foreigner I was ultimately of little interest to either.

V on the other hand, had never done this particular ride. Her working (and quite incorrect) assumption was that the road on the Guatemalan side of the border would be much the same as the British-made one on the Belizean side. And the idea of saving a whole day appealed to her. So I was overruled, but allowed to stop at a Chinese supermarket in San Ignacio to get some Durley's Parrot aged rum. The driver even loaned us some local currency for this.

Darkness enveloped us as the mini-van shuddered slowly along this deeply rutted highway. Occasionally you could see the light of a candle glowing amidst the trees on either side of us. In terms of palour and general agitation V now resembled our German chum, whose earlier nervousness looked in hindsight like an well-honed instinct for self-preservation.

V decided to make cheerful conversation with the driver. He clearly had a gun stashed away under the passenger-side dashboard, and repeatedly reached out to touch it. Suddenly the glare of fast-approaching headlights appeared in his mirror. "Don't worry," he said, "It's probably just my boss. He's angry because I'm late."

V shot me an "I'm so sorry!" look and prepared for the worst. We were overtaken by a big white SUV, possibly a Chevy Blazer. It pulled in front of us and stopped and our own driver followed suit. A stocky, lighter-skinned man with a pistol at his waist got down from the SUV and climbed into our mini-van pushing the driver over to the passenger side. At no stage did he acknowledge our presence. The two men started to argue noisily as the newcomer took over at the wheel and started to follow the other vehicle. V still looked like the German, but he had never quite lost the power of speech.

Lacking in basic social skills he might have been, but el jefe turned out to be the same sort of unusually obliging and unencroaching sort of individual as his now chastised employee, and his earlier anger appeared to derive from the latter's inability to keep up with him (time had been wasted in the Belizean "duty-free" zone) which had undermined their habitual convoy approach to the jungle crossing. We were driven to Santa Elena (near the causeway across to Flores) and we had one last moment of uncertainty when they drove us into a compound with a corrugated iron gate which was slammed shut and locked behind us by two men that had clearly been warned of our arrival. This turned out to be just another measure for our own security.

We and our bags were then transfered to another, smaller bus and taken to the muddy thoroughfare from where the overnight coaches set off for the capital. Sadly there were no "first class" services left at this hour. As we had used up the last of our cash settling up with 'shotgun tours' I had to wander off in search of an ATM. The first one I found was actually just a collection of wires sticking out of a hole in the ground: the entire machine had been wrenched from its location in a small booth off the street. Fortunately the next one was still hanging in there.

As is normal on these "second class" services the ayudante had sold a number of numbered tickets himself, so departure was delayed whilst passengers that had bona fide tickets bought at the office (ourselves included) squabbled with the interlopers. In the end I finished up right at the front in the ayudante's own seat (the guy from the office insisted), with V a few rows behind surroudned by tropical snorers. All the losers in the seat war were positioned on white plastic stools along the aisle. I drifted in and out of sleep listening to the amusing chatter between the driver and the ayudante, who bantered hard to keep themselves conscious for the next six hours.

Later, having safely arrived in Antigua with all our gear, we learned that V's brother Oscar had been in a mini-van in Petén the week before which had been sprayed with bullets as it tried to flee a roadblock set up by forest bandits.

Thursday, December 22, 2005

Tuesday, December 20, 2005

Decision Support

I read in the New Scientist last week how the makers of mass cinema entertainment now have a new software "decision aid" that seems remarkably capable of predicting which movies will bust blocks and which ones will bust studios and careers. All you have to do is feed an artificial neural net with information relating to the following seven parameters:

- The star value of the cast

- The age rating of the film

- The time of release relative to competing features

- The quantity of special effects

- Whether or not the film is a sequel

- And the number of screens it will open in.

Panzita Verde

The English climate has not deterred V from experimenting with the cultivation of aguacates (avocado plants).

This can be achieved by spearing the upper dome of the stone with halved cocktail sticks and then suspending it, flat side down, in a tumbler of water. We now have a little row of these rather alien-looking contrivances on our bedroon window sill. The first couple of weeks' immersement were unpromising, but now each of the stones has stretched a thick white root (rather like a mouse tail) down towards the base of the glass and one even has a fragile green shoot emerging from the widening vertical crack down its middle.

This can be achieved by spearing the upper dome of the stone with halved cocktail sticks and then suspending it, flat side down, in a tumbler of water. We now have a little row of these rather alien-looking contrivances on our bedroon window sill. The first couple of weeks' immersement were unpromising, but now each of the stones has stretched a thick white root (rather like a mouse tail) down towards the base of the glass and one even has a fragile green shoot emerging from the widening vertical crack down its middle.

Wednesday, December 14, 2005

Assortative

An adjective that is likely to crop up in connection with blogs sometime soon, if it hasn't already.

Assortative networks are those where similar nodes are more well-connected to each other than dissimilar ones − and one aspect of this similarity may itself be well-connectedness.

Nature published an article this week which threw some light on the peculiar professional ties between rap artists. Although a milieux noted for its collaborative nature, there are fewer collaborations between the most connected artists compared to other musical genres (and other celebrity subcultures such as Hollywood). This is perhaps a sign of intense commercial rivalry tinted with gangland mores.

That one creative group within our culture is more or less assortative than another is possibly not that interesting in itself, but combine this metric with others and a whole field of interesting investigations opens up:

Assortative networks are those where similar nodes are more well-connected to each other than dissimilar ones − and one aspect of this similarity may itself be well-connectedness.

Nature published an article this week which threw some light on the peculiar professional ties between rap artists. Although a milieux noted for its collaborative nature, there are fewer collaborations between the most connected artists compared to other musical genres (and other celebrity subcultures such as Hollywood). This is perhaps a sign of intense commercial rivalry tinted with gangland mores.

That one creative group within our culture is more or less assortative than another is possibly not that interesting in itself, but combine this metric with others and a whole field of interesting investigations opens up:

- Are more assortative artists creatively and commercially more successful?

- How much of their creative ouput derives from connectivity as opposed to what they could have achieved on their own?

Maya Mural

Another major find from the dig at San Bartolo (Petén) − a 9m x 1m mural said to date back to 100BC which depicts the establishment of the physical world.

Tuesday, December 13, 2005

The Count of Monte Cristo

There have been an awful lot of movie adaptations of the novels of Alexandre Dumas, and this is certainly not the most awful of them all.

There have been an awful lot of movie adaptations of the novels of Alexandre Dumas, and this is certainly not the most awful of them all.It cares as much − or possibly even less − for historical realism as Pirates of the Caribbean. That director Kevin Reynolds had a hand in movies like Red Dawn, Waterworld and Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves should remind us that he isn't accustomed to adding much depth to his material.

James Caveziel returns to his stock role as charismatic otherworldly innocent, but this time learns the eighteenth century equivalent of Kung Fu from the Abbé Faria (Richard Harris) whose head appears one day through the tiles in the floor of Edmond's cell in the Chateau d'If.

In terms of pacing and structure it's rather like an Italian opera − except without the music to amplify your emotional responses. As a boy I used to watch a cartoon version of this yarn, but had forgotten enough of the synopsis to make this an entertaining enough way of becoming reacquainted with it.

Friday, December 09, 2005

World Mayor

Our neighbour Álvaro Arzú, ('el canche') has come third in the World Mayor contest, behind the first citizens of Athens and Toronto − a feat which may entitle him to claim the title of Latin America's premier city boss. Mayor before he was Guatemala's President from '96-2000, Arzú stood again for his old job in 2004.

The task he faces in Guate may appear immense, but he's likely to have less of that running up the down escalator sensation than his former political ally President Oscar Berger.

75% of the norteamericanos' marching powder may pass through Guatemala, but 10% of all cocaine that arrives there stays: the narcos are keen to sow local usage by paying their contacts in Guatemala in drugs rather than cash.

High-level lawlessness became the norm under Berger's now fugitive predecessor Alfonso Portillo, and organised criminals have now not only penetrated almost every institution, they have set up a parallel state similar to the one that emerged in Colombia back in the '80s: traffickers offer loans, host parties and help with funeral expenses.

The task he faces in Guate may appear immense, but he's likely to have less of that running up the down escalator sensation than his former political ally President Oscar Berger.

75% of the norteamericanos' marching powder may pass through Guatemala, but 10% of all cocaine that arrives there stays: the narcos are keen to sow local usage by paying their contacts in Guatemala in drugs rather than cash.

High-level lawlessness became the norm under Berger's now fugitive predecessor Alfonso Portillo, and organised criminals have now not only penetrated almost every institution, they have set up a parallel state similar to the one that emerged in Colombia back in the '80s: traffickers offer loans, host parties and help with funeral expenses.

Wednesday, December 07, 2005

Hotel Rwanda

In a very brief visit to Kigali in 1998 (which did not extend beyond the airport) President Clinton described the mass killings in Rwanda four years earlier as "the most intensive slaughter in this blood-filled century we are about to leave." (Philip Gourevitch has estimated that Tutsis were dying at an average rate of 333 an hour during the summer months of massacre back in 1994. )

In a very brief visit to Kigali in 1998 (which did not extend beyond the airport) President Clinton described the mass killings in Rwanda four years earlier as "the most intensive slaughter in this blood-filled century we are about to leave." (Philip Gourevitch has estimated that Tutsis were dying at an average rate of 333 an hour during the summer months of massacre back in 1994. )"In such countries genocide is not too important", Francois Mitterand had earlier observed; his government had consistently supported the Hutu Power dictatorship. Yet for those of us at a safe distance from it, the lasting importance of this most intensive of slaughters remains the set of lessons that it can teach us about individual (and international) accountability and blame.

The first challenge is to understand how this particularly virulent variety of identity politics evolved in the first place. In Terry George's Hotel Rwanda there's a bar conversation in which a local man informs a foreign journalist that the Belgians purposefully engineered two distinct tribes in the colony based on prvailing notions of racial morphology. This is at best a radical simplification of the historical background.

Before reading Phillip Gourevitch's We wish to inform you that tomorrow we will be killed with our families the best account I had read was Kapuscinski's. The Polish journalist's take on the context could be summarised thus:

- Unlike every other African state there is hardly any genuine ethnic diversity in Rwanda. In fact, there is just one tribe, the Banyarwanda, which is split into two social castes, known historically as the Hutu and the Tutsi

- After independence the Belgians sponsored a regime which to them looked progressive because it overturned the old Tutsi-dominated feudal system, but was in fact a wobbly and paranoid Hutu-dominated dictatorship that eventually sought a final solution to its post-colonial difficulties.

Gourevitch's version is similar but more complete in terms of detail during each key period:

- There were once two separate peoples in pre-colonial Rwanda: a stocky Bantu people from the south (Hutu) and a lanky Nilotic people from the north (Tutsi). The original inhabitants of this mountainous little country were cave-dwelling pigmies called the Twa that now account for just 1% of the population

- Whatever ethnic distinctions that originally existed were soon diluted to the point of meaninglessness as Hutu and Tutsi intermarried and came to share the same language

- The distinction evolved into a largely sociological one: identifying the place of each individual in the feudal state

- When Africa was carved up in Berlin in 1885 the borders of Rwanda, unlike many of the other colonies, essentially preserved the pre-colonial socio-political realities

- European racial science incorporated a body of ideas known as the Hamitic myth (based on the story of Noah's son Ham) which appeared to justify the enslavement of darker Sub-Saharan peoples and in this instance the right of the Tutsis to lord it over the Hutus

- When the Belgians introduced ethnic identity cards in 1933 mobility between the two groups effectively ceased

- By then many of the colonists had started to favour the Hutus whose political subjugation to the minority Tutsis seemed to echo the fate of the Flemish in Belgium

- Ethnic animus began to surge in the second half of the twentieth century, especially when rogue intellectuals allied to President Habyarimana's Hutu dictatorship systematically fostered the idea of Hutu supremacy, carefully inverting the Hamitic myth to this end.

As the Tutsi were traditionally herdsmen while the Hutu were poorer cultivators, Gourevitch draws on the biblical myth of Cain and Abel to throw light on this particular fratricide. Yet throughout the book he appears to struggle with the issue of blame; as an American Jew he is acutely aware of the precedents, but clearly finds this instance of mass inhumanity rather harder to pin down.

For a start there's no obvious prime instigator in the Hitler or Pol Pot mould. Into that gap step aggregate culprits - Hutu supremecist broadcasters, cynical neocolonialists, and slightly more tenuously, the 'international community' and of course, the French. Then there are all the local structural features of Rwandan society: impunity, cronyism, ethncity, feudalism, Hamitism etc. However, cultural factors such as the rise of art and technology have an solid alibi here which might lead us to question the extent of their role leading up to the Nazi Holocaust.

Gourevitch also describes how the rural populations in Rwanda run a kind of swarm-attack neighbourhood watch system (something similar operates in Alotenango near our home in Guatemala) and speculates whether the unthinking communal response to the order to "do your work" was in some senses an inversion of this social mechanism.

"If everybody is implicated, then implication becomes meaningless" Gourevitch admits, whilst insisting that those that planned the genocide intended it to appear planless − a spontaneous popular response to the President's assassination − and worked hard in the months afterwards to further desensitise those outside observers already inclined to view it as indistinguishable from the general messiness of African tribal history.

Hotel Rwanda shows us the actions of one man who joined the ranks of the righteous by dent of denying the imperative so many other Hutus chose to obey. Like Oscar Schindler Paul Rusesabagina carried an admission card to the camp of the perpetrators, and was in his professional life a similar wheeler-dealer that stored up favours with a nexus of petty bribes.

In the end Rusesabagina gave sanctuary to around 1000 Tutsis in the Hotel Mille Collines, some of them wives and family members of the Hutus Power politicians that were leading the killings outside. The hotel manager's bourgeois ordinariness belied what Gourevitch praises as a "rare conscience." It seems that many who participated in the genocide also protected some Tutsis, as if to exonerate themselves for the killings. Survivors have been inclined to blame these individuals more as their actions appear to betray an awareness of the difference between right and wrong that others claim to have lost amidst the pressure to conform.

Rusesabagina's story is made-to-measure for a cinematic narrative about these almost incomprehensible events as it takes place in comparatively civilised isolation from the worst of the carnage, yet clearly imparts the ethical choices available. His character and actions make for an interesting contrast with those of humanitarian groups who flocked to Central Africa in the aftermath and ended up being, in Gourevitch's words, "exploited as caterers to the single largest society of fugitive criminals against humanity ever assembled". $1bn was spent on the Hutu refugee camps in Zaire, a "rump genocidal state" whose occupants (many still terrorised and militarised by Hutu Power thugs) thus enjoyed an equivalent average income of twice that of the remaining occupants of the ravaged country they left behind. Many of the Hutus did eventually return, thus posing a problem that the Germans and the Jews never really had to face on a large scale - post-traumatic cohabitation.

One key piece of luck that Paul Rusesabagina and his dependants benefitted from was the government's oversight in not disconnecting his fax line. In the film we see him calling the head office of his Belgian employers, Sabena, but in fact he made calls direct to the French government, the military outfitters of the Hutu génocidaires. One of the most striking scenes in the movie is Paul's speech to the hotel's guests where he advises them to call up all their foreign friends: "You must tell them what will happen to us... say goodbye. But when you say goodbye, say it as if you are reaching through the phone and holding their hand. Let them know that if they let go of that hand, you will die. We must shame them into sending help."

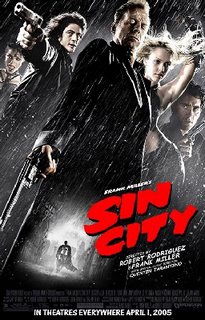

Sin City

The ciphers of the Western I understand well enough, but the same can't be said for pulp-noir mythology: What exactly are these pastiche retro-futures trying to tell us about contemporary America? It bothered me when I watched Batman Begins and it did so again when I turned to Robert Rodriguez's Sin City.

The ciphers of the Western I understand well enough, but the same can't be said for pulp-noir mythology: What exactly are these pastiche retro-futures trying to tell us about contemporary America? It bothered me when I watched Batman Begins and it did so again when I turned to Robert Rodriguez's Sin City.Bizarrely I felt I'd come a step closer to breaking the code when I watched Brian Sewell touring the Senate rooms of Siena last night. The frescoes on the walls depict two alternative visions of civil society: one governed by manifestations of all the virtues, the other presided over by their wicked inversions.

So perhaps these dark modern fantasies betray a pre-modern fear of evil ruling in parallel. They certainly flaunt a very medieval carelessness with anachronism and chronological time.

Sin City grabs your attention and holds it in a powerful grip for about an hour. Thereafter interest steadily slackens. The movie's on-screen style is exhilarating, but ultimately no substitute for good dialogue and storytelling.

In order to give artist Frank Miller co-director status Rodriguez had to resign from the Directors' Guild. He then worked hard to recreate the edits and textures of Miller's graphic novel taking the comic-book physics he explored in the Mariachi series to their logical conclusion. He has also borrowed some of the visual techniques his buddy Quentin Tarantino explored in Kill Bill. (Tarantino guest directed a sequence here with Benicio del Toro and Clive Owen.) It's a film you should see if you are interested in the latest blue-screen wizardry.

As for the pulp-noir dystopia - my own preference is for those that are more obviously shunted into the future such as Blade Runner or the graphic novels of Enki Bilal.

Tuesday, December 06, 2005

Everything Happens for a Reason

If that little platitude is part of your cosmological outlook then calamitous events like the Boxing Day tsunami should force you to scrutinise it quite closely.

Last night BBC1 aired a stunning documentary by Kevin Sim on the great wave and its aftermath: Tsunami:7 Hours on Boxing Day. Sim gently pushed a rather interesting notion: that animists encode the behaviour of Nature rather better than monotheists.

The last hundred or so indigenous inhabitants of the Andaman Islands were expected to have been wiped out by the wave, but in the end not a single one perished. Spotting the sudden retreat of the tide and interpreting it as a tilt in the relationship between land and sea, they immediately anticipated a violent return of the wet element and headed inland for cover. Less 'primitive' settlers on the islands were less fortunate. Indeed across the region observant Hindus, Muslims and Christians all struggled to comprehend the enormity of the disaster as it occurred and tended to internalise its meaning afterwards as part of a narrative of moral castigation.

One of the most striking images in the whole film was a little dog sitting, gaze-down, in a pile of debris. The animal was so obviously depressed that it made you wonder how canine consciousness deals with such devastation and loss.

For me one of the big lessons from 9-11, 7-7 and the tsunami is that if your morning starts with something unusually bad happening, always assume that things are going to get a lot worse: don't be one of the people that get taken out by the second plane/wave or hop on the bus to get away from the Tube bombers.

It was a bit of an accident that prevented us from going to Thailand last Christmas. I had found what I thought was a good deal on a last minute flight to Bangkok, but V insisted that I allow her to spend a morning calling up some of the agencies she'd used in the past in order to see if she could better it. One of these was Journey Latin America, who duly informed her that they only handle westbound flights. Rather than acknowledging the error and hanging up, V decided to check what it would cost us to go back to Guatemala for Christmas, something that until that moment she had vehemently opposed. That's how we ended up spending Boxing Day in Antigua and not somewhere in the path of the tsunami.

It killed 227, 000 people - roughly a quarter of the death-toll of the Rwandan genocide in 1994, which will be the topic of a future post.

Last night BBC1 aired a stunning documentary by Kevin Sim on the great wave and its aftermath: Tsunami:7 Hours on Boxing Day. Sim gently pushed a rather interesting notion: that animists encode the behaviour of Nature rather better than monotheists.

The last hundred or so indigenous inhabitants of the Andaman Islands were expected to have been wiped out by the wave, but in the end not a single one perished. Spotting the sudden retreat of the tide and interpreting it as a tilt in the relationship between land and sea, they immediately anticipated a violent return of the wet element and headed inland for cover. Less 'primitive' settlers on the islands were less fortunate. Indeed across the region observant Hindus, Muslims and Christians all struggled to comprehend the enormity of the disaster as it occurred and tended to internalise its meaning afterwards as part of a narrative of moral castigation.

One of the most striking images in the whole film was a little dog sitting, gaze-down, in a pile of debris. The animal was so obviously depressed that it made you wonder how canine consciousness deals with such devastation and loss.

For me one of the big lessons from 9-11, 7-7 and the tsunami is that if your morning starts with something unusually bad happening, always assume that things are going to get a lot worse: don't be one of the people that get taken out by the second plane/wave or hop on the bus to get away from the Tube bombers.

It was a bit of an accident that prevented us from going to Thailand last Christmas. I had found what I thought was a good deal on a last minute flight to Bangkok, but V insisted that I allow her to spend a morning calling up some of the agencies she'd used in the past in order to see if she could better it. One of these was Journey Latin America, who duly informed her that they only handle westbound flights. Rather than acknowledging the error and hanging up, V decided to check what it would cost us to go back to Guatemala for Christmas, something that until that moment she had vehemently opposed. That's how we ended up spending Boxing Day in Antigua and not somewhere in the path of the tsunami.

It killed 227, 000 people - roughly a quarter of the death-toll of the Rwandan genocide in 1994, which will be the topic of a future post.

Monday, December 05, 2005

Without a Trace

Sin Dejar Huella (2000) is a watchable Mexican road movie about two young women with very different backgrounds driving south away from testosterone trouble up in Chihuahua. (Comparisons with both Thelma and Louise and the vastly better Y Tu Mamá Tambien are inevitable.)

There's more tension in their relationship than in any of the scenes of flight and pursuit. The more unlikely member of the duo is a con-woman played by fey Spanish-Italian beauty Aitana Sánchez-Gijón, who at the time was President of the Spanish Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. The movie won the Latin American Cinema award at the Sundance festival in 2001, but the principal pleasure of viewing this feminist non-thriller comes from the moving Mexican scenery and three spectacular locations: a colonial hotel in Ticul, a grand old Yucatecan hacienda and a perfectly formed cenote.

There's more tension in their relationship than in any of the scenes of flight and pursuit. The more unlikely member of the duo is a con-woman played by fey Spanish-Italian beauty Aitana Sánchez-Gijón, who at the time was President of the Spanish Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. The movie won the Latin American Cinema award at the Sundance festival in 2001, but the principal pleasure of viewing this feminist non-thriller comes from the moving Mexican scenery and three spectacular locations: a colonial hotel in Ticul, a grand old Yucatecan hacienda and a perfectly formed cenote.

Friday, December 02, 2005

Transhumanism

Last weekend V and I chatted about how technology has become increasingly embedded in the lives of children. Whilst we still think of most of the gizmos in our own lives as tools – to be used and discarded according to need – it seems to us that for many teens and pre-teens they are becoming more like clothes: something it's hard to imagine carrying on daily life without.

Kurzweil and others speak of the coming singularity, the moment when human-computer interface has become so intimate that tool and user are in a sense one super organism. This pre-destined merger of human and machine intelligence is tending towards a point of transcendence that Kurzweil forecasts for the middle of the twenty-first century. Along the way he might speak of a cure for global poverty, but what he is really on about is a cure for the human condition – and the particular human in question is clearly Ray Kurzweil.

This notion of transhumanity is dangerously detached from humanism and exposes the key fault lines in futurist thinking. Alarm bells ring every time I hear someone naively express the view that technology in itself is neutral: "It's the uses it's put to that determine the ethical implications.." (Even Richard Dawkins prefers to argue that it's Science that is neutral, whilst technology begins once the Science is applied.) If it was, it would be one of the few areas of our culture that could be thus kept so neatly separate from the minds of those that imagined it.

V and I have both grown up with computers and other technological tools and she in particular has a knack for rapidly scouting out the new possibilities offered by each as it emerges. But she also has a keen sense of what is lost (as I learned when she wholeheartedly rejected the concept of in-car sat nav) and that is something that younger people who have never fully experienced the 'problem' without the technological solution will increasingly find it hard to form an objective view on.

As today's parents rush to bring up lots of little transhumans (because intimacy with technology is seen as a marker of potential), they might give some thought to nurturing that part of their children's imagination you might call their inner luddite. Not to the point of actual gizmophobia, just suitably sceptical about Kurzweil-style techno-narcisistic over-enthusiasm.

Kurzweil and others speak of the coming singularity, the moment when human-computer interface has become so intimate that tool and user are in a sense one super organism. This pre-destined merger of human and machine intelligence is tending towards a point of transcendence that Kurzweil forecasts for the middle of the twenty-first century. Along the way he might speak of a cure for global poverty, but what he is really on about is a cure for the human condition – and the particular human in question is clearly Ray Kurzweil.

This notion of transhumanity is dangerously detached from humanism and exposes the key fault lines in futurist thinking. Alarm bells ring every time I hear someone naively express the view that technology in itself is neutral: "It's the uses it's put to that determine the ethical implications.." (Even Richard Dawkins prefers to argue that it's Science that is neutral, whilst technology begins once the Science is applied.) If it was, it would be one of the few areas of our culture that could be thus kept so neatly separate from the minds of those that imagined it.

V and I have both grown up with computers and other technological tools and she in particular has a knack for rapidly scouting out the new possibilities offered by each as it emerges. But she also has a keen sense of what is lost (as I learned when she wholeheartedly rejected the concept of in-car sat nav) and that is something that younger people who have never fully experienced the 'problem' without the technological solution will increasingly find it hard to form an objective view on.

As today's parents rush to bring up lots of little transhumans (because intimacy with technology is seen as a marker of potential), they might give some thought to nurturing that part of their children's imagination you might call their inner luddite. Not to the point of actual gizmophobia, just suitably sceptical about Kurzweil-style techno-narcisistic over-enthusiasm.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)