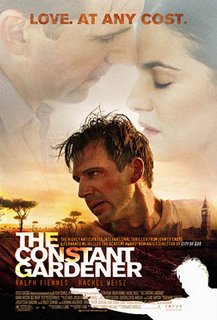

Phew. I was beginning to wonder when I'd get to see such an excellent movie again. There might be a certain flimsiness in the detail, but as both a love story and a captivating parable about the treatment of the poor and powerless by the rich and powerful, The Constant Gardener is highly effective.

Phew. I was beginning to wonder when I'd get to see such an excellent movie again. There might be a certain flimsiness in the detail, but as both a love story and a captivating parable about the treatment of the poor and powerless by the rich and powerful, The Constant Gardener is highly effective.Mike Newell was originally slated to direct, but perhaps misguidedly chose to jump ship for the new Harry Potter movie. So instead this project benefited from the visual style and energy of the man that gave us City of God and City of Men.

O.P. Rachel Weisz is a shoe-in for these sort of feisty, idealistic roles these days. She combines being good on the eye with being genuinely fascinating to watch, which is more than can be said for many of her Hollywood contemporaries.

Le Carré wrote the novel in his home in Cornwall. In an interview on the DVD he explains that he originally wanted to "go for oil" but was concerned that that would have been "too much on the nose". Then an old Africa hand convinced him to go for the Pharma industry instead. Later, on location for the film director Fernando Meirelles engaged the chairman of a pharmaceutical giant on its subject matter. It was of course all nonsense he was reassured, but when pressed, the executive admitted that his firm would feel obliged to cover up any fatalities arising from clinical trials in the Third World. "We're not killing people that wouldn't be dead otherwise," is how one implicated bureaucrat puts it in the movie.

I used to think that one of the things that would make living permanently out in Central America unbearable would be the nagging drone of cruelty and injustice surrounding whichever private sanctuary I chose to install myself in. A large part of this is indeed the kind of unfairness and insensitivity that you can get righteously angry about from places like Cornwall − if every country on the planet had a lifestyle like ours we'd need three Earth's worth of resources to keep it up. As it is, we need a a global economy that is structured to the disadvantage of the poorest nations. However, seventeen years of direct experience of one small part of the developing world has also revealed to me a far less unequivocal reality that varies from the following notions which appear in almost all the literature about it:

- In such nations a few rich and corrupt individuals are systematically taking advantage of the needy.

- Foreign investors and multinational corporations have only their own profits in mind.

- The selfishness of the exploiters contrasts with the networks of mutual assistance that exist amongst the poor masses.

And, when you talk to some of the locals there's an important corollary that persistently crops up: "What this place needs is a strong man to get rid of all the corrupt politicians, narcs, bandits, warlords etc."

Sure, there's truth in all of these, just not the whole of it. For me the worrying thing about the most painful aspects of the millieux is their origin in ordinary life. More often than not, the people that arouse my most severe righteous anger in Guatemala are a lot less well off than us. Not men in suits, indigenous or foreign. The fact is that the cruelty, the insensitivity and the reflexive selfishness is close to all pervasive.

I can't claim to be an expert on game theory, but I think I know enough to suggest that a small group of 'hawks' would find it quite hard to thrive in a society otherwise dominated by out and out 'doves'. By all means bring in your strong man, but for every crook that is 'cleared out' there would be hundreds of understudies waiting their chance to step in. The roots of kleptocracy are often deeper than many appear to allow for.

I'll l come back to this topic of deep-level corruption (or non-collaboration) later when I tackle Jared Diamond's Collapse, where I will no doubt also trot out my conviction that the trouble with the USA is that it is essentially a rich Third World country. In most of the rest of the rich world we have learned, perhaps uniquely in human history, to treat our peers humanely, and judging by the evidence of this story many of us yearn to extend that favour yet more widely.

There's a really key moment in the film where a choice has to be made: Tessa wants to offer a lift to a family that are about to walk 40Km back to their village. Horticultural hubbie Justin argues that he has to prioritise her health and anyway, the aid agencies are there to tone down the ambient hardship. Later, in a scene that deliberately echoes the first, we see Justin shouting "this one we can help!"

I guess this is the essence of V's personal approach out there− direct personal intervention rather than donation through third parties; dealing with individuals not situations. She's suspicious of organised charity (or rather of organised anything!), convinced that it often unwittingly helps the undeserving (a view that was perhaps born out by the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide).

The 800,000 people living in the unsanitised shacks of Kibera − that Meirelles acknowledges as poorer than the favelas of Brazil − got themselves a new wooden bridge out of this production. Maybe some of the cast and crew donated a portion of their earnings to African charities, but more importantly, perhaps their transient presence in some way made a difference to the lives of the people they encountered there.

The dedication in Le Carré's novel is to a lost friend "who gave a damn".

No comments:

Post a Comment