"No animal will accept the justice of being punished for following its instincts..."

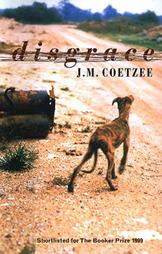

"No animal will accept the justice of being punished for following its instincts..."The state of disgrace at the core of Coetzee's Booker-winning novel settles on the life of Cape Town academic David Lurie. At the time we join his story he believes that he has sex, parenthood and animal welfare all sorted, but this mid-life equilibrium soon crumbles around him and he is propelled on a difficult journey, taking in abasement and then self-abasement, before resigning himself to the fact that there will be no going back.

Lurie is at once likeable and loathable, but both in small measure. He achieves a rather mediocre sort of redemption by apparently accepting that the "higher life" might well have been an illusion of youth, fortune and comparative privilege. There's an overriding mood of pessimism in the novel, but no real sense of despair. The whole thing is rather too self-contained, too oblique. Whatever you think of Michel Houellebecq's depiction of the menopaused male's condition, I find its frankness thrilling compared to the layers of symbolism and suggestion with which Coetzee coats his meanings.

It might be an honest book, but honesty cloaked in this much artifice is somehow dishonest. You feel you know what Lurie is thinking on the very relevant issues of sex and race, but the narrator contrives ways of denying us direct access to these inner observations (even though we are told that the disgraced professor has "never been afraid to follow a thought down its winding track").

I suppose some might argue that this is just the point. Lurie feels like an imposter in society, because his instincts are mediated through an aspiration to inhabit a world of more or less pure ideas. He's out of touch with himself. This comedown will bring him closer to both being and relating to"a certain type of person...with fewer complications".

Like Saturday Disgrace takes one man's situation and uses it to expansively touch on many different topics of local interest, yet fails to illuminate any of them in a strikingly original way. As this man is white, middle-aged and erudite, one has to suspect that the author elected not to stray too far from representing his own sensibilities. And as in McEwan's novel, none of the other characters are drawn in great detail. The psychology of Lurie's violated daughter Lucy seems especially sketchy.

This book was recently chosen by an illustrious literary panel as the best English-language novel to come out of Britain (and former colonies, US excepted) in the past 25 years. So I read it with high expectations, only to find that while I can like and admire it, it's not a book I can love.

Coetzee deploys some peculiar metaphors, such as when Lurie declares himself to be cold, as if a goose had trodden on his grave.

Incidentally, I learned last night that the Captain of the overturned ferry The Herald of Free Enterprise was called David Lewry. He too was disgraced and suspended after setting sail with the bow doors wide open.

No comments:

Post a Comment