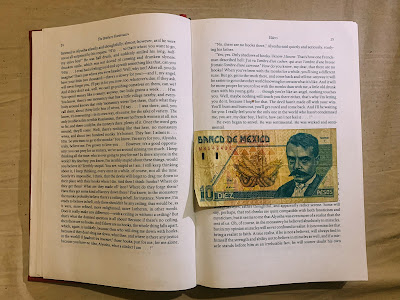

Both last week's viewing of Heretic, plus the debate surrounding whether a telly adaptation of One Hundred Years of Solitude has been a bit of a fool's errand, have reminded me of this somewhat lighthearted passage in The Brothers Karamazov, which also touches on why we believe the things that we do.

In the movie, High Grant's Mr Reed tries to upset the belief system of the two visiting missionaries by pointing out a few of the logical problems and what he calls iterations.

In this illustrated bit of Dostoevsky's novel, Alexei has to listen to his father Fyodor Pavlovich pondering whether the devils in Hell really have hooks, and if so...

Even as he rabbits on, the old man senses that his son will be unperturbed. And this will tend to be because Christianity achieved more than one important transformation in its early history. Not only was it adopted by the ruling classes, the state, it also absorbed enough of the classical neo-platonic tradition to make it appealing to educated, reasonably rational people and semi-watertight against what we might refer to as Socratic assault.

You'll see what I mean if you do a Google search for overtly 'Christian' reviews of Heretic. These critics have answers for most of Mr Reed's challenges to their beliefs (even if many seem happy to throw the Mormons under the bus.)

A rationalist assault on religious stories might unsettle, confuse or even annoy a person whose beliefs are wholeheartedly irrational, but for the more learned listener questions like 'does Hell have a ceiling?' slip off their sophisticated cerebral armour — which has been fashioned to suspend the import of such enquiries somewhere liminal between the literal and the non-literal.

Or, as Doestoevsky's narrator puts it a page or so further on...

"In the realist, faith is not born from miracles, but miracles from faith."

In this novel there are also nested mini-narratives which would translate badly onto the small screen, such as a coffin which refuses to go inside a church. Show it and it becomes historical fact, rather like showing Mary getting an unexpected visit from Archangel Mike in a TV movie.

Christianity, like Gabo's masterpiece, more or less depends on everything being literal only within a kind of folk universe. The high priests of the faith have one foot in this world, but also one foot in another, where they consider themselves immune to the biting logical animus of men like the late Christopher Hitchens.

Some of the readers of Cien Años de Soledad will be believers, in ghosts for example. Maybe for them Hell also has a roof.

García Márquez was a Marxist-Leninist materialist, so he almost certainly was not. (This is why his flavour of magical realism differs from that of say Isabel Allende, who is clearly more open-minded towards the immaterial. Her novels are not just representations of provincial storytelling of the common sort.)

Meanwhile, Doestoevsky further notes that young Alyosha would probably have ended up as a socialist if he were not a believer, "for socialism is not only the labour question or the question of the so-called fourth estate, but first of all the question of atheism, the question of the modern embodiment of atheism, the question of the Tower of Babel built precisely without God, not to go from earth to heaven."

The same basic urge, flipped.

No comments:

Post a Comment