October

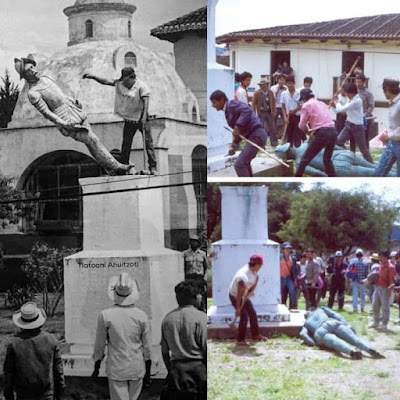

12, 1992 was marked in San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, by the

toppling of a statue of Diego de Mazariegos, conquistador.

Resistance

to foreign conquest is seemingly coded into the Mayan DNA. They gave

the Spanish their first and bloodiest of noses when the first shiploads

showed up on the mainland, and a pattern of often violent push back

continued into the twentieth century.

This had a couple of interesting features which are worth remarking on. Firstly,

during the Caste Wars — ending 1901 — the insurgents were as likely to

target their rage at the Hispanic population — those who'd long been

busy blending, assimilating — as the Criollos of 'purer' European

descent.

Secondly,

although they seemingly rejected the non-'original' civilisation

imposed on them, they typically did so in the name of the Middle Eastern

prophet Jesus of Nazareth, who had kind of tagged along for the ride

with Columbus. (A socially-radical Jewish thinker fully committed to a

non-violent approach to imperialism…but they sort of skipped that rather

significant bit of his teachings. You won’t find ‘by any means

necessary’ in the New Testament.)

These

Maya retained the sense of having been politically and culturally

overrun, while filtering out the promise of eternal reward, which they

regarded as the best part of the whole bad situation.

Contrast the indigenous peoples of North Africa and elsewhere who were conquered by the Arabs from the seventh century onward.

The

recent Mohammed Salah British Museum meme has a relevant double-edge to

it, as the joke is both that much-loved Mo is standing before small pieces of

Egypt taken by light-fingered British colonialists, while at the same

time he may be unaware that he is himself the representative of an

invasive culture that came and stole the entire place; The Full Montu,

so to speak.

In effect, he's one of those long term assimilators that the Mayan indigenous resistance would likely have singled out for punishment.

In effect, he's one of those long term assimilators that the Mayan indigenous resistance would likely have singled out for punishment.

Arabs

have spent far more of recorded history as colonial oppressors than as

the victims of incursions from outside, rolling out conquests which

featured many of the most repellent features of imperialism wherever or

whenever it has occurred, such as brutal mass enslavement — particularly

of black Africans — yet they consistently get a free pass on this today,

not just in western academia, but also in the history that is generally

understood in the conquered populations, like Egypt or indeed, Persia.

It

seems rather obvious that it will remain difficult to engage in

rational debate about some of the most pressing issues in our

contemporary world until that blanket is removed.

Islamism,

Jihadism and so on are leftovers of that first 'inflationary period'

after the Caliphates formed, but they are also, crucially, products of

contact with twentieth century totalist systems of thought which first

emerged in Western Europe.

A

grown up approach to this threat to the liberal democratic way of life

requires us all to ditch the hackneyed models and simmering hatreds

peddled by the intellectually-bunged up ideologues of Left and Right.

As I mentioned in part one, the first Iberian arrivals in this hemisphere came with a package of intentions and plans for the future. Religious and secular motives were often intertwined and difficult to unravel, both then and now, yet it had always been an abiding feature of European Christianity since the religion had been adopted by Constantine, that the majority understood on some fundamental level that a separation of the things of Caesar and the things of God was not only possible, but desirable — and the Maya appeared to have grasped this concept when they started cherry-picking which parts of forced Europeanisation would need to go.

There

have been and will continue to be theocratic variants of all the

monotheistic faiths, but Islam will always be the most problematic in

this respect, because there are ultimately no real protections for lay

society, with the political and spiritual far harder to prize apart.

This

was perhaps Mohammad's great innovation, and its legacy has been

complex. It possibly explains why many North Africans see themselves as

'Arabs' in a manner that would seem bizarre indeed to Mexicans or

Central Americans, who would never refer to themselves as 'Spanish', not

even the ones who have retained a fully European DNA admixture.

They

appear unable to conceive of themselves as peoples still living with a

legacy of colonial conquest, because they cannot find a way in their

minds to separate the political imposition from the religious one.

So,

unlike the Maya, they'll rarely conclude that while it is a good thing

to have adopted a foreign religion, all the other stuff that came with

it needs to be considered with a less worshipful frame of mind.

And

alongside this cultural constraint, we see how the Arabs and their

useful idiots abroad consistently blame the West in their rhetoric for all forms of colonialism, which helps maintain the smokescreen.

Their

task has been made easier by the fact that, more than any other time in

history, Western intellectual life is now dominated by cultural streams

gushing out of the USA, and Americans are often by nature, historically

myopic and somewhat self-obsessed.

No comments:

Post a Comment