The media, vaccine manufacturers and Scottish politicians are currently content to stoke up a pre-Christmas panic about the diabolically transmissible nature of Omicron.

Viz yesterday both Nicola Sturgeon's 'tsunami' simile and that report about the inmates at a Hong Kong quarantine hotel who had somehow passed the virus between their rooms without ever having left them.

Early data does seem to suggest that Omicron is significantly more transmissible than even Delta 2. But when one looks at the data with a level head — at the household level as opposed to the modelled mass-population level — one finds that the contagion potential is perhaps less seasonally chilling than one might have immediately suspected.

This is not smallpox or even bubonic plague. You can live in the same house as someone carrying this pathogen and still have a better than 4 in 5 chance of not picking it up.

This thread on Twitter reflects level-headedly on the threat from a South African perspective.

Relative to the community case rate covid-19 hospitalisation in the country remains low, at least compared to previous surges. The death rate is especially low.

One can imagine all sorts of reasons why the likes of Pfizer would be encouraging people to have not just three but four jabs now, just to be safe. And as I said a week or so ago, we should begin to start engaging our critical faculties in booster mode when the fourth wave and any measures to flatten its curve are anticipated — especially when the suggestions are being made by entities with skin in the game.

The South Afican data suggests that Omicron is 5x more antibody-evasive than Beta, but it remains unclear whether individuals possessing relevant antibodies — as say up to 95% of Brits — end up with symptoms little worse than a bad cold. T cells still come into play and may continue to suppress the more damaging consequences of infection. In the UK the current estimate of government advisors is that Omicron is 25-50% less severe.

So far muscle aches, headaches and lethargy are the most prevalent clinical manifestations of an Omicron infection, which leads me to suspect that I might not even notice that I'd had it.

Plenty of footballers in the UK are flagging as positive right now, but the current rules state that they all need to be tested every day. How many would even have been aware of the virus?

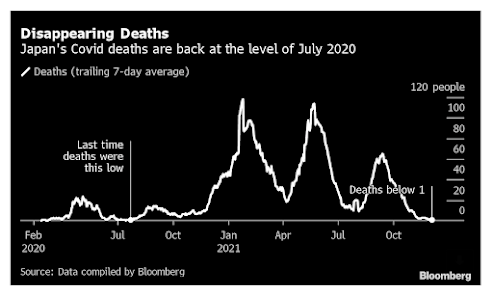

Behind the more naked (private sector) scaremongering, one will also perceive the voice of scientists fretting over the phenomenon illustrated by this chart...

Milder, faster diseases can end up killing more people than deadlier, less transmissible ones. That there is truth in this is confirmed by the history of SARS-Cov-1, a virus that tended to terminate 10% of its hosts. But in absolute terms, its numbers were 'disappointing' relative to the early dread.

Yet these charts are subtly forcing us to think that Omicron resets the pandemic to zero, when in fact many of the key vulnerabilities have shifted over the course of two years and governments have had a chance to advance beyond the one-size-fits-all policy package.

This time, protecting the vulnerable while allowing a milder mutation to pass rapidly through the vaccinated population could be markedly less of a kamikaze option.

We can see in Japan for example that a set of controlled measures without lockdown has recently led to a drop in case numbers and an even more dramatic suppression of fatalities, and in many different localities the relative death rate (or even ICU rate) amongst those infected has been tailing off for some time.

Do the un-vaccinated* deserve some sort of protection? I know what I would be inclined to say were it not for the fact that the clogging up of hospitals by these recusants is likely to have a knock-on effect for the standard of care everyone receives, and will also provide the media and others with further grounds for propagating trepidation across the community.

And regardless of everything said in this post the drift towards complacency in Guatemala is extremely worrying. Even before Omicron I was anticipating a new wave here in late February/early March — it is the heat, not the cold, that drives people indoors and into mass events here.

The patchy and variegated nature of the vaccine roll-out, coupled with the apparent lack of an imminent, comprehensive booster programme suggests that here, as elsewhere in Latin America, 2022 could be extremely difficult for all sorts of reasons.

* I'm referring who have had a decent chance to get the basic shots and have no socio-demographic excuses to make.